Our Stories

Philanthropy is a process of discovery. Supporters and scholars learn and grow together. These stories illustrate the meaningful relationships that enrich our campus community and beyond.

Discover what inspires our community of supporters.

For the Love of Listening

Harry Smith Glaze Jr.’s remarkable collection of more than 2,000 rare opera recordings is available at UC Santa Barbara, where it will be preserved and shared through the Library’s Performing Arts Collection thanks to his daughter, Cathy. She also established the Harry Smith Glaze Jr. Fund for the Performing Arts to ensure its long-term care and accessibility.

Continue Reading For the Love of Listening

Basic Science is Key

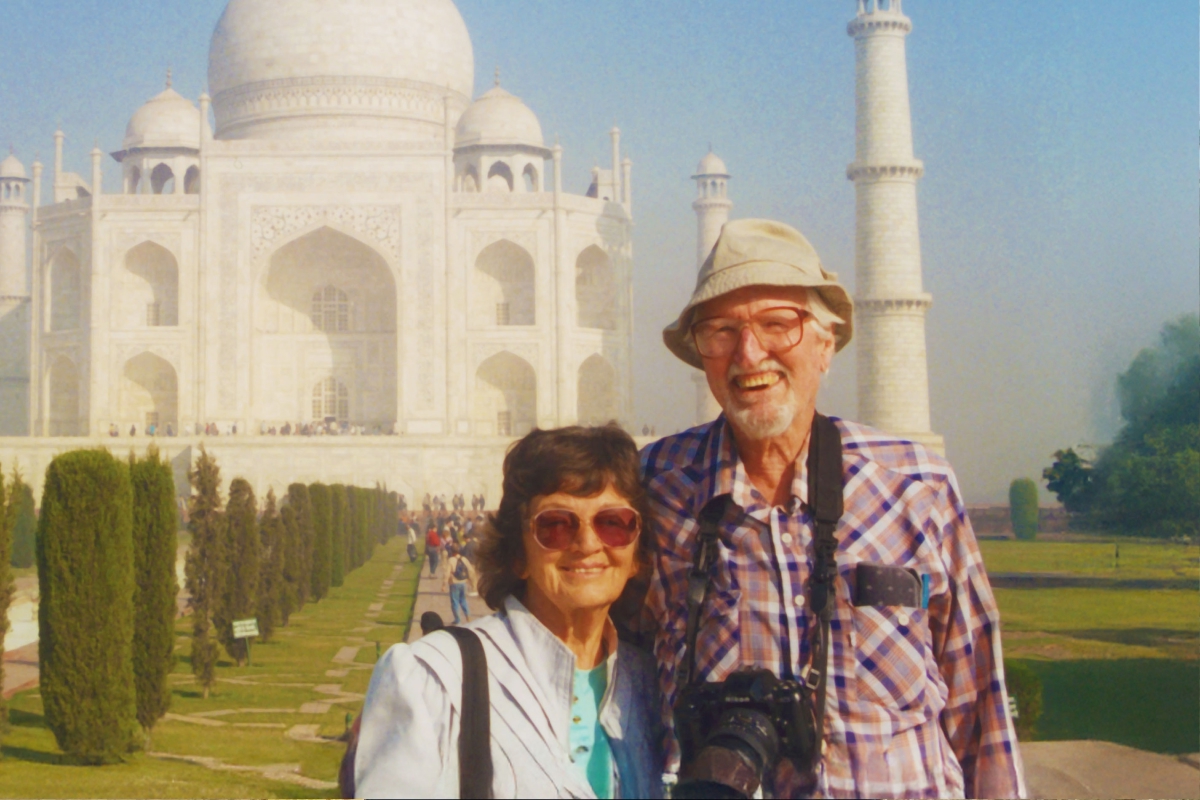

Sam Handelman ’77 and Barbara Pettersen have made one of the Department of Mathematics' first legacy gifts. Their support champions fundamental science and provides flexible resources to help graduate students and faculty pursue research.

Continue Reading Basic Science is Key

A Life in Languages

Professor Harvey Sharrer’s lifelong dedication to medieval Iberian literature lives on through a bequest that supports graduate students in Spanish and Portuguese studies at UC Santa Barbara. His gift represents a career defined by discovery and mentorship.

Continue Reading A Life in Languages

In Their Names

David McDonald ’85 has created four named scholarships and an endowed fund for the UCSB Library to honor his family's lives. His gifts ensure lasting financial support for students, connecting his family’s legacy to future generations.

Continue Reading In Their Names

The Flywheel Effect

Chuck and Missy Sheldon and Loi and Adele Nguyen have established endowed chairs to advance innovation and entrepreneurship in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Technology Management. Their gifts are part of the broad base of support that has transformed the department into a powerhouse of entrepreneurship and business education.

Continue Reading The Flywheel Effect

When a Home Becomes a Legacy

When Erika Davis decided to downsize, she turned her home into an opportunity to help students. Through a charitable gift annuity with UC Santa Barbara, she secured her retirement, created the Richard and Erika Davis Scholarship, and left a lasting legacy for students.

Continue Reading When a Home Becomes a Legacy

Preserving Campesino Culture

Gilbert García H’90 and Marti Correa de García have donated 61 Mexican prints to UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design, & Architecture Museum, honoring the resilience and collectivism of campesino culture. Their gift, along with endowed support for research and exhibitions, preserves the stories of migrant farmworkers and celebrates their enduring contributions.

Continue Reading Preserving Campesino Culture

Stone Soup

Mercedes Millington, Alec and Claudia Webster ’75, and Peter Schuyler help to expand access to UC Santa Barbara’s Santa Cruz Island Reserve. Thanks to their collective support of field-station improvements and education opportunities, every visitor can experience the island’s beauty and contribute to its preservation.

Continue Reading Stone Soup

A Transformative Gift

UC Santa Barbara Athletics has received a transformative $15 million anonymous gift — the largest in its history — to revitalize facilities and support major upgrades at Caesar Uyesaka Stadium, home of UCSB Baseball.

Continue Reading A Transformative Gift

Publisher, Leader, Benefactor

Sara Miller McCune H’05 is a pioneering publisher, dedicated philanthropist, and longtime UC Santa Barbara leader. Her far-reaching support across the social sciences, Arts & Lectures, the Library, and more reflects a steadfast belief in the power of research and the humanities to strengthen democracy.

Continue Reading Publisher, Leader, Benefactor

Education for All

Dr. James Stretch ’78,’84 and Dr. Sybil Carrère ’78 are leaving a lasting impact on UC Santa Barbara through a planned gift that will support aquatic biology students. Their generosity helps ensure that more students can pursue hands-on scientific research.

Continue Reading Education for All

Access for All

The ¡Viva el Arte de Santa Bárbara! endowment is securing a vibrant future for free, bilingual arts programming across Santa Barbara County. Its community of philanthropy ensures that performances celebrating Latin American music and culture will continue to inspire connection, pride, and access to the arts in perpetuity.

Continue Reading Access for All

Everyone Can See the Stars

Larry and Dee Franks, longtime Friends of KITP and familiar faces at Chalk Talks, have ensured a legacy of discovery with one of KITP’s first unrestricted bequests. Their planned gift reflects decades of connection to UC Santa Barbara and will support the institute’s greatest needs well into the future.

Continue Reading Everyone Can See the Stars

Beyond the Classroom

Matthieu ’87 and Marie-Anne Duncan are expanding hands-on learning through their support of the Division of Social Sciences Dean’s Investment Group and Education Abroad Program. Their generosity gives students the chance to apply classroom knowledge, from managing investments to studying in France.

Continue Reading Beyond the Classroom

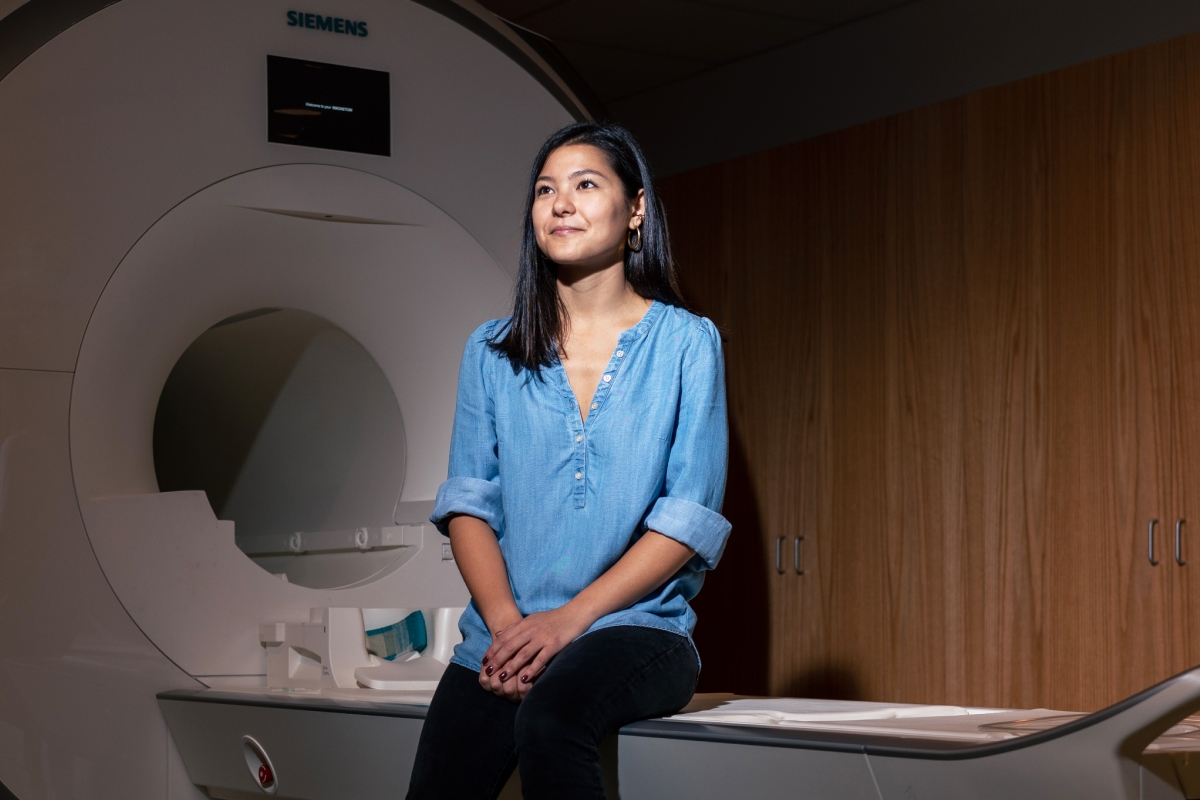

Study Women

Investment from the Robert N. Noyce Trust and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative is empowering the Ann S. Bowers Women’s Brain Health Initiative at UC Santa Barbara to close the gender gap in neuroscience. Their support fuels groundbreaking, collaborative research to transform our understanding of how the brain changes across a woman’s life.

Continue Reading Study Women

In Tribute to Glen Henry Mitchel, Jr.

A $1 million matching gift in memory of Glen Henry Mitchel, Jr. inspired a wave of support for the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, culminating in $2 million to advance the Mitchel Postdoctoral Scholars Career Development Fund. This collective tribute honors Glen’s lifelong passion for physics.

Continue Reading In Tribute to Glen Henry Mitchel, Jr.